I work with learning-centered and mission-driven teams to shape clear, effective content — whether you’re navigating change or building for the long term.

New leadership, shifting strategy, growing pains, and high-stakes launches are part of the work, and so is the day-to-day craft of making ideas land.

My work spans two core areas:

Vision & strategy

For leaders who know something isn’t working yet and want to get it right before moving forward. I help you step back, clarify the problem, and create direction that fits your goals and constraints.

Content and communication approach (what does it look, feel and sound like)

Engagement and audience research (who’s your audience and what do they want and need)

Message and narrative development (what’s the story)

Competitive and landscape analysis

Creative

For organizations that need high-quality work that connects, I translate strategy into compelling content that understands real-world constraints.

Writing (long- and short-form)

Storytelling and editorial content

Content planning and creative direction across media

Making complex ideas accessible and engaging

If you’re looking for creativity, momentum, and a partner who can think and make at the same time, I’d love to connect.

A practical approach

to creative

problem-solving

Most of my work starts in moments of change. Something feels unsteady, pressure is high, and you don’t want to rush the wrong solution. My process is designed to slow things down just enough to get them right, then get moving again. I’ve developed this approach over 15 years leading creative teams and producing creative work across edtech, media, and the arts. This method paired with my service-oriented leadership style works for both small, scrappy teams with modest resources and large, cross-functional organizations with big budgets and lots of stakeholders.

Step 1: Investigating your problem and determining your goal

First, we are going to discuss your problem a lot. I’ll interview the people closest to the work. I’ll listen to the people who would benefit from a solution to the problem. I’ll do a bunch of reading and research to dig deeper. My goal at this stage is to understand the problem and the people affected by it as well as I possibly can.

During all of this, I intentionally refrain from thinking about solutions. Solutions are distracting right now. They give you the comfort of progress before you’ve uncovered the strong foundation it requires.

The risk of getting the problem wrong

In 2025, I worked with an edtech company navigating a sudden, high-profile policy announcement that created internal momentum (because the company’s offering was relevant for the new policy) before there was an understanding of what the change actually meant. Leadership reacted quickly, mobilizing departments and teasing speculative initiatives in an effort to stay ahead of the moment and turn the policy shift to their advantage.

Stepping in, I advised pausing execution and reframed the situation as a question rather than an opportunity. What immediate problems did the announcement create? How could we best solve those problems for our users? I reviewed the executive order, examined the public conversation surrounding the announcement, and spoke directly with people who would be most affected. This surfaced a critical insight: the central problem was the panic the uncertainty had caused. The policy announcement was void of details and didn’t carry many practical implications yet.

The challenge was not how to capitalize on the news, but how to respond responsibly in the absence of clear implications. The company needed a way to acknowledge the moment, signaling awareness, consideration and empathy, while buying time to think.

The solution prioritized restraint and clarity. I quickly produced a simple, steady response that communicated three things: we were paying attention, we understood the questions educators were facing, and we were committed to engaging thoughtfully once the landscape became clearer. The goal was to create credibility and trust.

This work reinforced a core principle of my approach: the most strategic move is often to slow down, define the real problem, and respond with precision. This reduces wasted effort and keeps teams focused. It also means a better solution because you can’t find a good solution if the problem is wrong.

My 1961 kitchen solved the problem “install a range hood,” not “capture smoke while cooking.” That’s how you end up with a hood that's not directly above the stove — and a smoky kitchen.

Step 2: Time to make pots

Once I have a thorough understanding of the problem — that’s that strong foundation — it’s time to think about solutions. The goal here is quantity. Are you family with the Pottery Class Paradox?

The first ideas that bubble up are going to be the most obvious, the ideas already floating around in the collective consciousness, the ideas that have already been tried out. We need to flush those ideas out by writing them down. I want to unearth the subconscious’s ideas. The ideas that are truly novel and interesting. Even if they are wacky or unfeasible or only solve a part of the problem, I want them on the page because they might inspire the winning idea. 25 ideas is usually a good goal during the brainstorming phase. Not because we’ll use most of them, but because the good ones rarely show up first.

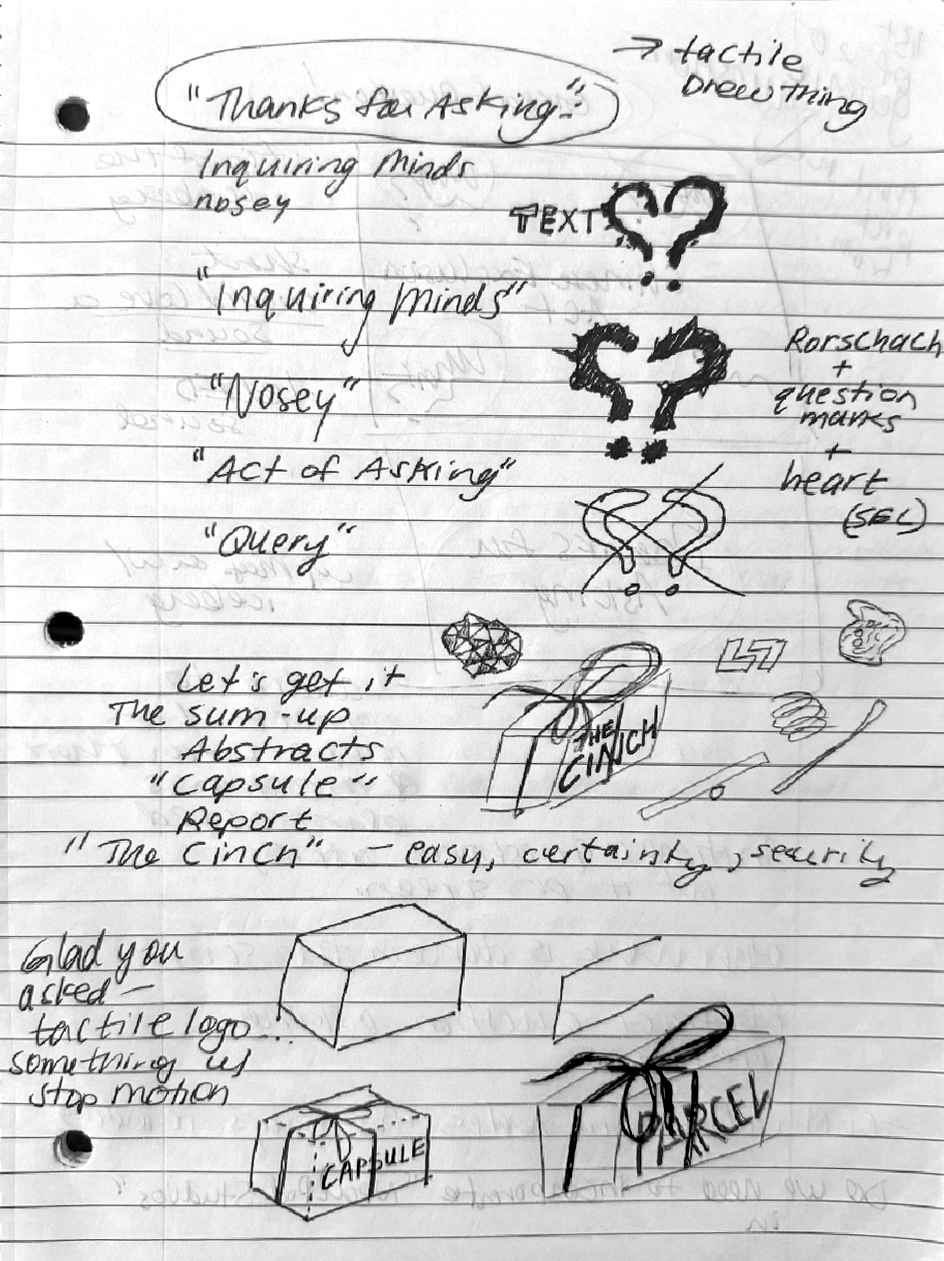

Everyone brainstorms differently. For me, it’s handwritten journaling. Writing by hand slows me down, and there’s a cool interplay between what I’m writing and what I’m thinking. Sometimes there’s even a third layer: what I’m thinking about what I’m thinking. I enter a flow state of multiple levels of thought. This is how I tap into truly new ideas.

Once they are out, I whittle them down to the ones worth exploring.

Step 3: Pop quiz!

Now we test. We could call it prototyping or creating a Minimum Viable Product.

Recently after two-too many cups of strong coffee, I came up with what I thought was a brilliant idea for a new luxury print magazine. Sure, the magazine industry is on life support, but who doesn’t love a gorgeous, glossy magazine-object d’art? Imagine a literary journal that’s also a window-shopping experience — where each story is accompanied by an artist-made object, beautifully photographed in a still-life, with a link to the artist’s website in case you’re feeling spendy.

Luckily, when I had this idea, I didn’t start by building the whole thing out. After researching magazines I admired and talking to the people I thought would read this new creation, I designed a super-simple landing page. The goal was to collect emails and create a mailing list. Just enough to see if the idea had a pulse. It didn’t. And that was valuable information. That’s how I like to work: real-world signals over internal enthusiasm.

This type of prototyping occurred all the time when I led the creative team at Flocabulary, an ed tech company that produces educational hip-hop songs and videos. Before we scheduled the vocalists and rappers and the space in a studio, we needed to validate that the song was going to work. That’s why we made tons of references. My phone is still full of embarrassingly-bad voice memos of me, not a rapper or a vocalist, rapping and singing early versions of songs. Because somebody had to do it.

Here’s an example:

Step 4: Choosers be choosey

After we have the test/s, we need to decide on the direction our solution will take. Earlier, we were expansive. No idea was bad. Now, we are critical. We poke holes. We pressure-test. We look for future problems while they’re still cheap to fix.

I’d rather adjust early — because of budget, timing, or marketing realities — than pretend constraints don’t exist and pay for it later. Usually one or two ideas survive this stage.

Once we make a decision about what we are moving forward with, it’s time to execute for real, then scale.

Step 5: The very important unsexy stuff that leads to success

Success requires three things:

Internal team buy-in (better yet: enthusiasm) and smooth collaboration

Careful planning of time, money, people, and any other resources.

Marketing. It doesn’t matter how great our creation is if the right people aren’t hearing about it.

Internal team buy-in (better yet: enthusiasm) and smooth collaboration

I build team cohesion and enthusiasm by giving people real ownership, not just direction. I try not to tell people what to do — instead, I give them a clear goal and ask questions so they can figure out the best way to get there. This leadership style comes from my training as a life coach. When people shape the solution, they take pride in it and commit to it; it becomes their work, not just an assignment.

I empower people to do their best work by creating a safe space. By “safe space,” I mean a work environment where the nervous system isn’t constantly on edge. Everyone is creative, but stress kills creativity. The best creative thinking happens when stress is managed, expectations are clear, and people feel trusted to experiment and allowed to make mistakes. This spirit also helps teammates connect with one another, which supports the health of the team as a whole.

Careful planning of time, money, people, and any other resources

Here is where we want overcommunication, systems, processes, documentation, and a team bought into the idea that it’s mission-critical to follow the systems and processes that are in place. This gets increasingly important as the size of the operation grows. Here is where we need a project manager (or PM team, depending on scale) and the right project management tool for the job. For small projects, a spread sheet and a calendar can work. But for bigger initiatives, we can use Asana, Airtable, Click up, etc.

I always refine the PM system with input from the team because it needs to work for them. Measure twice, cut once, if you know what I mean. (I mean: let’s get the project management system right at the very beginning to avoid suffering through technical debt down the line and ultimately needing to rework it).

I’m a big fan of the RACI.

Marketing

A great product doesn’t matter if the right people never hear about it. Ensuring that high-quality, accessible, and inclusive content actually reaches the people it’s built for is part of the work — not an afterthought. When content, product, and marketing are aligned, each strengthens the others: the product is better understood, the story is clearer, and the impact is deeper. That kind of alignment creates momentum and trust, not just visibility.

My experience spans both marketing and product, which strengthens each discipline and improves alignment between them. Because I understand how both sides operate, I’m able to help teams collaborate more effectively and build work that’s cohesive from strategy through delivery.

Step 6: Ship it

Now we press the green button, and we get results. I worked at Flocabulary for eight years and helped shape the company’s culture, brand identity, and product. Flocabulary was ultimately acquired twice, evidence of the value I helped create. Check out some of my work at Flocabulary below.

Here’s another example with some real numbers. In spring and summer 2025, I led content and email strategy for a wellness-focused edtech startup at a make-or-break moment. Working with a very small budget and team, I built a simple, sustainable content engine that included an interview-based video series and practical curriculum resources for educators. Over about 10 months, email open rates rose from the low-20% range to the mid-30s, click-through rates more than doubled (peaking around 10%), and the email list grew by roughly 8%. Content marketing shifted from a checkbox to a meaningful way to support educators and drive engagement.

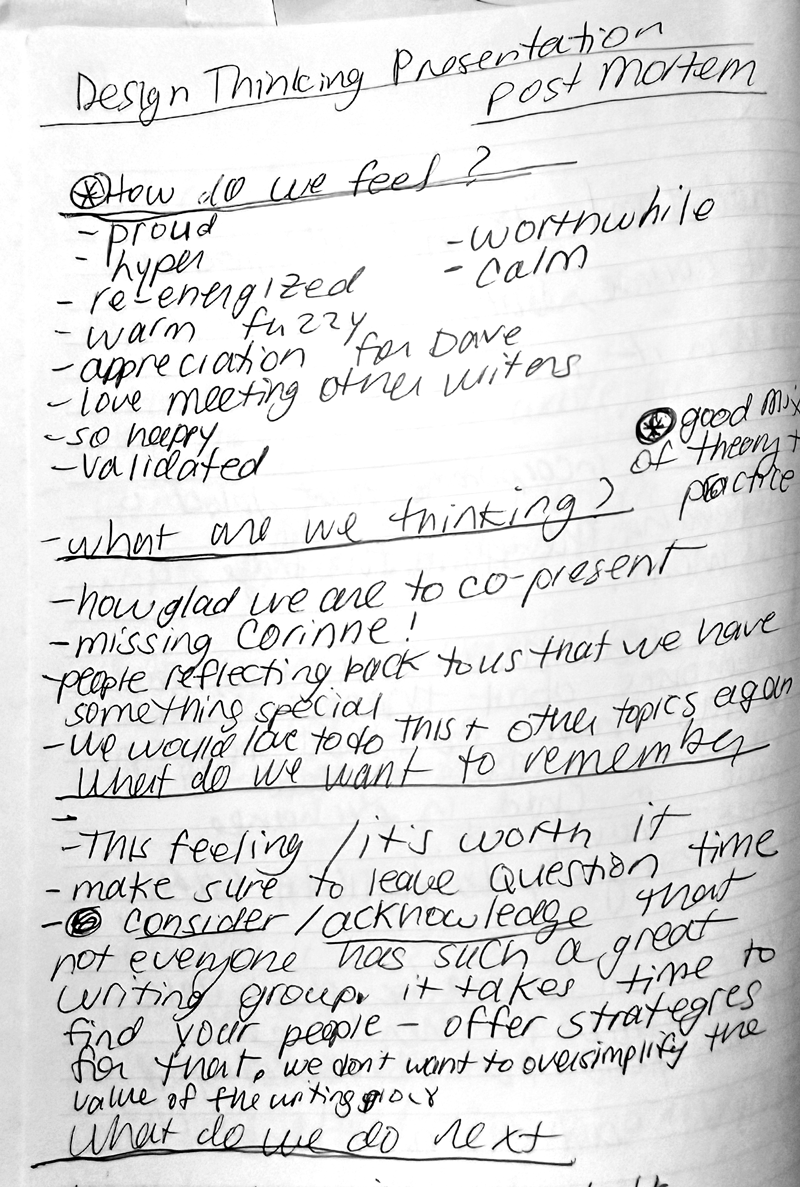

Of course, the story doesn’t end here. We collect feedback, study the data, and run a postmortem, reflecting on what worked, what didn’t, and what we’d change next time. A good postmortem turns experience into knowledge, so each project begins smarter than the last.

In the end, we leave with a solution to our problem, deeper expertise, a more cohesive team, and an audience that actually heard the message. Soon enough, there’s a new priority, a different challenge, an unexplored problem. And I love a problem.